Palonera

467 Reviews

Translated · Show original

Palonera

Top Review

73

"You smell like home!"

said the young man sitting across from me on the old carpet, between us the hot tea, in his eyes a "How can this be?".

Home was far away in Afghanistan, in a country he had left, had to leave with the girl who was now his wife, and the child she was carrying.

That was three years ago, almost four.

They had to leave when the killing came closer, when the nights exploded in a cacophony of noise and light, when more and more houses became ruins and the inhabitants buried beneath them.

"How could we have stayed?" he asked, looking at me as if I actually had an answer.

For a while we were silent, watching the boy who played obliviously with the colorful blocks that had been in the bag that always came with me, which made his eyes shine in the face of the treasures it contained time and again.

He was the reason for my visits, the reason I sat here, here with him and his father, who was so young yet already so old, only twenty years old, yet already twenty years, whose eyes had seen more than was good for him.

"He would not survive," he said, "not where we come from. There is no life for children like him there."

For children who did not hear, who could not walk and did not speak, children who were different and just like him.

The boy, who was now searching for my eyes, inquisitive, questioning, waiting for my smile, the reassuring, teasing one, with which I took a block and held it behind my back until he laughed and tugged at my sleeve.

"Give me! My - want to play!" he gestured - slowly, uncertainly, so very clearly.

I gave him the block, took two others, built a tower with him, higher and higher, until it fell and the stones rolled to his father's knee.

He smiled, lovingly and proudly at his son: "It is good that he is here, that we are allowed to be here. I am grateful. And I miss Afghanistan so much. It was not always like this, you know?!"

And he began to tell about his village with the six houses, about the people who lived there and the livestock with them - "everyone had a few sheep and chickens, some even had cattle, for which there was not much feed near the village.

In summer, when it was very hot and no rain fell, we went up into the mountains with them, my father, my uncle, and I. To where it was a bit cooler, where grass still grew, salty, spicy grass, brown and gray from dust, but feed for the animals.

Sometimes we had to walk far until we found something, so far that we did not return home at night. We stayed with the animals on the mountain and sat in the evening around the fire, which smoked and smoldered and almost suffocated us, but warmed us and on which we brewed coffee in old tinware.

We chewed on licorice and smelled the warm, dusty fur of the animals, the dry herbs and the rocks, the smoke of the fire and ourselves in the coarse clothes that are so different from what one wears here.

The men told stories and I, still a boy, listened to them, stretched out by the fire, arms crossed behind my neck and my gaze in the stars, which were so bright and so close and so many, so many, you cannot count them, never, ever.

It was very quiet up there, only sometimes you heard one of the animals in the darkness and another that answered - and the wind of course, the wind that was always there.

It was beautiful there, you know?! Wild and beautiful and peaceful - no one ever thought of war or of not being there anymore. I thought it would always stay that way, I would always stay there like my father and his father and all the fathers before. And now I am here," he concluded, still looking at the boy, his son.

His wife had been in the room while he was telling, quietly, unobtrusively, lighting a little incense in the corner, the scent drifting over to us and mixing with the dark tea.

We were silent again.

It was time for me - the next child.

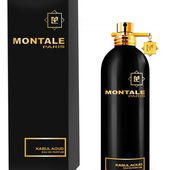

In my bag, I found "Kabul Aoud," the tube still half full.

I placed it next to his tea and left.

Home was far away in Afghanistan, in a country he had left, had to leave with the girl who was now his wife, and the child she was carrying.

That was three years ago, almost four.

They had to leave when the killing came closer, when the nights exploded in a cacophony of noise and light, when more and more houses became ruins and the inhabitants buried beneath them.

"How could we have stayed?" he asked, looking at me as if I actually had an answer.

For a while we were silent, watching the boy who played obliviously with the colorful blocks that had been in the bag that always came with me, which made his eyes shine in the face of the treasures it contained time and again.

He was the reason for my visits, the reason I sat here, here with him and his father, who was so young yet already so old, only twenty years old, yet already twenty years, whose eyes had seen more than was good for him.

"He would not survive," he said, "not where we come from. There is no life for children like him there."

For children who did not hear, who could not walk and did not speak, children who were different and just like him.

The boy, who was now searching for my eyes, inquisitive, questioning, waiting for my smile, the reassuring, teasing one, with which I took a block and held it behind my back until he laughed and tugged at my sleeve.

"Give me! My - want to play!" he gestured - slowly, uncertainly, so very clearly.

I gave him the block, took two others, built a tower with him, higher and higher, until it fell and the stones rolled to his father's knee.

He smiled, lovingly and proudly at his son: "It is good that he is here, that we are allowed to be here. I am grateful. And I miss Afghanistan so much. It was not always like this, you know?!"

And he began to tell about his village with the six houses, about the people who lived there and the livestock with them - "everyone had a few sheep and chickens, some even had cattle, for which there was not much feed near the village.

In summer, when it was very hot and no rain fell, we went up into the mountains with them, my father, my uncle, and I. To where it was a bit cooler, where grass still grew, salty, spicy grass, brown and gray from dust, but feed for the animals.

Sometimes we had to walk far until we found something, so far that we did not return home at night. We stayed with the animals on the mountain and sat in the evening around the fire, which smoked and smoldered and almost suffocated us, but warmed us and on which we brewed coffee in old tinware.

We chewed on licorice and smelled the warm, dusty fur of the animals, the dry herbs and the rocks, the smoke of the fire and ourselves in the coarse clothes that are so different from what one wears here.

The men told stories and I, still a boy, listened to them, stretched out by the fire, arms crossed behind my neck and my gaze in the stars, which were so bright and so close and so many, so many, you cannot count them, never, ever.

It was very quiet up there, only sometimes you heard one of the animals in the darkness and another that answered - and the wind of course, the wind that was always there.

It was beautiful there, you know?! Wild and beautiful and peaceful - no one ever thought of war or of not being there anymore. I thought it would always stay that way, I would always stay there like my father and his father and all the fathers before. And now I am here," he concluded, still looking at the boy, his son.

His wife had been in the room while he was telling, quietly, unobtrusively, lighting a little incense in the corner, the scent drifting over to us and mixing with the dark tea.

We were silent again.

It was time for me - the next child.

In my bag, I found "Kabul Aoud," the tube still half full.

I placed it next to his tea and left.

29 Comments

Top Notes

Top Notes  Myrrh

Myrrh Cedar

Cedar Thyme

Thyme Heart Notes

Heart Notes  Coffee

Coffee Labdanum

Labdanum Patchouli

Patchouli Sweet clover

Sweet clover Base Notes

Base Notes  Gaiac wood

Gaiac wood

Aliana

Aliana Saemm

Saemm Taamii

Taamii Jensemann

Jensemann Caligari

Caligari Terra

Terra Rookie82

Rookie82 Irini

Irini Gusteau

Gusteau Berkantist

Berkantist